Note: MOTHER 2 will referred to throughout as EarthBound—just because I've played through the second game in the MOTHER trilogy almost a dozen times, and its title screen always said EarthBound.

Gosh. It's been a while, hasn't it?

I'll have you know I started working on a

MOTHER 3 writeup a few months after we finished our review of

EarthBound, but then some stuff came up and the enterprise found itself adrift in an authorial sargasso for the better part of two years. As far as I'm concerned, this puts us on excellent footing for the occasion. After all,

MOTHER 3, didn't materialize for more than full decade after the release of

EarthBound, and for years fans had every reason to believe the series would conclude with

EarthBound's "The End...?"

The

MOTHER 3 developmental timeline is a little murky: videogame news and previews were still confined to magazines through much of the late 1990s, so the armchair historian without access to a physical archive of

Nintendo Power, Electronic Gaming Monthly, and

GamePro issues from the period has to rely on the disparate magazine scans floating around the internet.

The records show that

MOTHER 3 was officially announced in 1996 at Nintendo's Spaceworld expo in Japan, but it wasn't until 1997 that North American fans found out it was coming as

EarthBound 64. I was in middle school then, and one morning the Mario-obsessed kid sitting two desks ahead of me in homeroom brought an issue of

Nintendo Power containing the first screenshots of

EarthBound 64.

Some

Nintendo Power scans give us a look at Nintendo's early plans for the title. Like

Super Mario Bros. had done,

EarthBound was taking the leap from 2D sprites and tilesets to a 3D engine. Moreover, it was being developed for the 64DD, a CD-ROM peripheral for the N64 scheduled to hit the Japanese market in late 1997. Nintendo suggested the game would follow on the heels of

Zelda 64 (later retitled

The Legend of Zelda: The Ocarina of Time), and projected a North American release sometime during 1998.

I can somewhat recall the discussions on the sections of the old

Nintendo Power message boards haunted by

EarthBound fans. (This was before

Starmen.net, you see.) We puzzled over the screenshots and devised elaborate theories based on the scraps of information we'd been given. So what did it all

mean, we asked. Was the main character supposed to be a cowboy now? What happened to Ness? How fared Eagleland? What were we supposed to make of that pile of

wreckage with the Onett billboard? Where was the game actually set? The old west? Some bizarre future? A fantasy world completely removed from

EarthBound?? And what about Pokey? What the hell happened to Pokey?

We waited for more news. And we waited. And we waited.

The 64DD kept getting delayed, and so did

EarthBound 64. Every so often

Nintendo Power or some other magazine would publish a blurb reminding us it was still on the way, but substantive new information remained scant. At some point in 1998, when it became obvious to everyone that the N64DD was a wind egg,

Nintendo announced that

EarthBound 64 was still on its way, but was being reformatted as a standard N64 cartridge game. At some point, the phrase "Fall of the Pig King" was added to its title. It disappeared from

Nintendo Power's Release Forecast page, and then reappeared. A playable demo was presented at Spaceworld in 1999.

And then in August of 2000, the news broke:

EarthBound 64 had been aborted. It was left to the unaffiliated gaming journalists to break

the news;

Nintendo Power never published an obituary.

EarthBound fans went through the customary rites of mourning. We signed petitions. We replayed

EarthBound and the "

EarthBound Zero" NES ROM. We mained Ness in

Super Smash Bros. We wrote fanfiction and drew comics for Starmen.net. We regressed from speculating about

EarthBound 64 back to pondering all of

EarthBound's imponderable mysteries and wondering if any of them would have been resolved by

EarthBound 64.

In 2002, we fans up at the news of a

MOTHER 1+2 compilation under development for the Gameboy Advance, which was

something, but only slightly better than nothing. (Even before game companies were habitually repackaging and reselling old classics on new systems, some of us were already sensing that being able to buy and play

Chrono Trigger on six different consoles/mobile devices wouldn't be quite the same as getting a new

Chrono game, and shouldn't be taken as an indication that one was on its way.) Some versions of the Japanese TV commericials claimed that the third game was still forthcoming as a GBA title. Itoi verified this in April 2003, but the project once again seemed to be in abeyance: for years there were no official annoucements, no release dates, no screenshots, nothing but hints and rumors.

2005 saw the first of two

MOTHER-related miracles. Eleven years after

MOTHER 2, nine years after the announcement of

EarthBound 64 and five after its cancellation, and three years after

MOTHER 1+2 teased it,

MOTHER 3 for the GBA was officially announced by Nintendo and slated for a spring 2006 release.

EarthBound 64 was being rebuilt almost from scratch, by

Legend of Mana developers Brownie Brown instead of APE. Much of

EarthBound 64's setting, cast, and scenario were carried over, but this was still like taking the script of a cancelled film, rewriting it, recasting all the actors and crew members, building completely new sets, and shooting every scene over again. How often do you see this kind of thing happen in

any medium? What else can you call it but miraculous?

The

first batch of screenshots were presented in February 2006, and they were beautiful. Sometimes you'll look at the preview materials for the sequel to one of your favorite games and be unpleasantly piqued by how

different it looks from the original, and can't help worrying it will be too dissociated from its antecedent to measure up to it. I don't think anyone could have felt any trepidation after their first look at

MOTHER 3. Pixel for pixel, it was the very image of the sequel an

EarthBound player would have envisioned back in 1995.

But as the Starmen.net crowd scintillated with anticipation, devoured all the translated press releases, and spread the news, Nintendo of America kept mum on

MOTHER 3. Their silence made patently clear that they had no intention of localizing it for North America. Though the GBA ROM was dumped mere days after the game's release in April 2006, there wasn't really much point in playing it if you couldn't read hiragana. I messed around with it for maybe fifteen minutes the week after itS release, and it drove me

crazy. Imagine having a flying car in your garage, but no ignition key. It exists, and it's sitting

right there, but there isn't much you can

do with it.

Then came the second miracle, which might have been even more unlikely than the first. The

EarthBound faithful already had a lot to thank Tomato (aka Clyde Mandelin) for. He was, after all, a co-founder of Starmen.net, the veritable Jerusalem to the English-speaking diaspora of Gutsy Bat seekers. He also happens to be a

career Japanese-to-English translator. Between his deep familiarity with the

MOTHER series and his professional chops, there was probably no living person on the planet more qualified to spearhead an English version of

MOTHER 3. What he and

his crew achieved, working pro bono during their evenings and weekends for almost two years, sets an implausibly high standard for fan translations. To get an idea of how much work went into it, go ahead and scroll through the

the project page. The lengths the team went through to make sure the thing was done right are positively staggering.

And so in October 2008—thirteen

years after

EarthBound first arrived in North America (and teased us with

this shit)—English-speaking fans could finally,

finally experience its sequel.

I'm curious to know how many times the translation patch has been downloaded. By Tomato's reckoning, it exceeded 100,000 downloads by the end of 2008. Even if we assume that only half that number would have actually paid forty bucks for a GBA cart, that's still 50,000 sales that Nintendo has obstinately affirmed and reaffirmed its disinterest in making.

I'm starting to think that Lucas was excluded from the new

Super Smash Bros. purely as a "fuck you, never" to pesky North American

MOTHER fans.

Though I was a diagnosed

EarthBound fanatic in 1997-8, and glad as I was at the news of a forthcoming N64 sequel, I had to admit being a little put off by the images from

EarthBound 64. I would have preferred it hadn't jumped on the 3D bandwagon, for one thing, but what bothered me was that there was nothing in the game's general aesthetic to mark it as the follow-up to

EarthBound. Take a look:

Had the magazines not identified it as

EarthBound 64, most readers would have guessed it was a totally unrelated game. And that had me a bit worried:

EarthBound's minimalist, cartoonish visuals, its psychedelic battle screens, and its off-kilter modern day setting were what distinguished it from all the other RPGs on the SNES, and I feared that a sequel which deviated so sharply from the original was bound, as it were, to be a disappointment. (In my mind then,

EarthBound was the first and only game in the series. Most North American fans were unaware of

MOTHER at that point.)

Nine years later, I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw the first images of

MOTHER 3: yes,

this was how it was supposed to be all along, I said. As far as I could tell, Itoi and his crew had taken

EarthBound 64 and reined it back in, restored it to what it was supposed to be. In other words, they'd repurposed it to be more like the

EarthBound I knew and loved.

But

MOTHER 3 is actually just as different from

EarthBound as the

EarthBound 64 screens suggested. We've already compared

EarthBound to

MOTHER and seen how many elements of the NES game were carried directly over to its SNES sequel.

MOTHER 3 looks a lot like

EarthBound, and behaves similarly: it's a legitmiate sequel, but the differences outweigh the similarities.

MOTHER is a riff;

EarthBound is a deconstruction;

MOTHER 3 is an inversion. It's the odd duck of the trilogy, and not because it's the one where the hero isn't a kid in a red baseball cap. It takes the expectations you bring to it from

EarthBound and turns them on their heads.

For instance: in

EarthBound (and

MOTHER), you pick up a phone and call Dad to create a new save file, and you check ATM machines to acquire the cash you've earned for defeating enemies in batte. In

MOTHER 3, both saving and money management are carried out by talking to frogs. In the first two games, you recover HP/MP by staying at hotels, and you revive fallen party members and cure status ailments by visiting hospitals. In

MOTHER 3, you do both by taking a five-second break in one of the many hot springs found throughout the Nowhere Islands.

From these two features, two themes are already apparant: the first is the heroes' reliance upon objects in the natural world to perform the same necessary RPG tasks that were carried out in previous games by patronizing modern technologies and services. The second is

simplification. By consolidating four locations/items into two (ATMs + phones = frogs; hotels + hospitals = hot springs),

MOTHER 3 asks its players to do a lot less legwork, a lot less searching around, and spend a lot less in-game resources (money, time) than in

EarthBound.

Though I hate to digress (full disclosure: this is a baldfaced lie), I've some SMPS omake I'd like to share with you. At this point I'm probably ever going to get around to editing the now-ancient writeup for

Final Fantasy VII (which is a shame, because it really is a helter-skelter mess). But at one point I did begin revising it, and I recently dug up a few paragraphs that were going to be added to version 2.0. They're actually germane to

MOTHER 3, so let's take a look:

Final Fantasy VII forms the second—and more radically transformative—half of Final Fantasy's liminal period. We use "liminal" to refer to the transitional gray area between the games we can classify as old-school Final Fantasy and new-school Final Fantasy. Think of it this way: look at Final Fantasy V next to VIII. The franchise transformed from one into the other within the span of only two games.

I won't pretend to recall verbatim all the 1997-8 message board chatter, but Final Fantasy VII seems to me to have inspired the very first schism within the North American sect of the Final Fantasy/SquareSoft faithful. Surprising as it may seem now—"Quite possibly the best game ever made," remember?—a lot of the stateside fans who had played the hell out of Final Fantasy I, IV, and VI looked at Final Fantasy VII and shook their heads. "This isn't the Final Fantasy that I know," they groused.

Why not? Was it the changes in the setting and tone? Was it the fact that it wasn't on a Nintendo console? Or was it just the annoyance of the self-declared O.G. at the perception that the object of his devotion has "sold out?"

There might be something to that last one. All signs suggest that SquareSoft anticipated (correctly) that Final Fantasy VII would attract a huge crowd of first-time Final Fantasy players overseas. Why wouldn't they try to make these players' first experience with the series as accommodating as possible? Final Fantasy VII wasn't designed for hardcore fans of the console RPG, but for "casual" players whose interests would be piqued by the pre-release media blitz. Square's object, then, was to take a type of game that tended to be arduous and unforgiving and make it more user-friendly and uncomplicated—and preferably without wholly alienating the existing fanbase.

So the party size has been trimmed down to three characters from four. The equipment screen has been reduced from "R-Hand/L-Hand/Body/Head/Accessory/Accessory" to "Weapon/Arms/Accessory." Each character only equips one type of weapon: now when you buy a new sword at the shop or find one in a treasure chest, you don't have to spend even a moment considering which party member to hand it to. The materia system—born of Final Fantasy VI's magicite/relic system—renders party members almost totally interchangeable with one another. All spells, battle commands, and stat bonuses can be equipped, unequipped, and traded between characters. Now the only things setting apart party members are:

1.) Their base stats

2.) The range of their weapons (short range and long range)

3.) Their unique Limit Breaks

Limit Breaks—the evolved version of Final Fantasy VI's obscure Desperation Attacks—are for the most part the major distinguishing characterstic between party members, and most of them do pretty much the same thing: "damage one enemy," "damage all enemies." There are a handful of healing and buffing Limit Breaks, but only a handful—and they only belong to Aeris, Red XIII, Cait Sith, and Yuffie. (One of whom becomes completely unusable halfway through the game, and another of whom is a secret character.)

In Final Fantasy V and VI, the ways in which you select and grow your party members has significant impact on your progress through the game. In VII, the two characters you pick to tag along with Cloud are much more a matter of personal taste than strategic importance.

There's a very fine line between streamlining something and dumbing it down, and it can't be said that Final Fantasy VII is innocent of the latter. But it's probable that the developers understood (correctly) that for many players, it was their engagement with a game's characters, setting, and plot that formed the basis of their affinity for console RPGs. The great success of VII's retooled and simplified design might be how efficiently it expedites players' access to the collateral narrative stuff for which they probably bought the game in the first place—and how it manages to do so without making all the random battles and materia management seem like a perfunctory necessity. (Like in Chrono Cross.)

Anyway.

EarthBound

EarthBound was already a fairly user-friendly piece of software (especially compared to

MOTHER), but

MOTHER 3 cuts players even more of a break. There's almost

never any ambiguity as to where you should go or what you should do: if you're not given explicit instructions as to your next move, someone in the vicinity will clearly spell it out for you. Just to make sure you don't get lost when your destination might be a wee bit unclear, there are actually arrows (well, arrow-shaped lizards) that will literally point you in the right direction. The environments are even smaller and more hemmed in than before. There are fewer enemies running around, and now almost none of them are randomly spawned; their positions in the field are scripted. You no longer have to worry about getting jumped by gang members or chased by sentient child-eating taxicabs while wandering around town (and there are only

two towns in the whole game). There are fewer items to keep track of, and the store menus will tell you exactly what they do (whereas in

EarthBound, you had to shell out money and then examine the item in your bag). Just about every dungeon (and the word "dungeon" must be used loosely in

MOTHER 3) contains a frog (save point), and many contain hot springs. Detailed maps for almost every area, including the haunted castles and Pigmask strongholds, are routinely handed over to you.

I have mixed feelings about these changes, sure. But if I had to fall on one side or the other of the streamling vs. dumbing down question, I'd be less inclined to say

MOTHER 3 is dumbed down. The "dungeons" are generally short and fairly straightforward, but I often found them hitting that narrow sweet spot between "what, that's it?" and "oh god there's MORE?" And there's no denying that

MOTHER 3's battle system and relata are much tighter than

MOTHER or

EarthBound's. There are fewer enemies running around, yes, but they're consistently

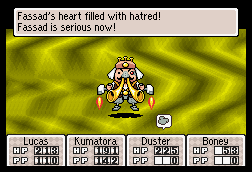

tough, and the boss battles are indisputibly the most challenging in the series. Even the combo system,

MOTHER 3's only new addition to the battle sequences, only serves to help you eke out victories against the likes of Mr. Generator, Fassad, and the Barrier Trio without having to spin your wheels on level grinds.

But in any case, these kinds of changes from previous iterations of

MOTHER serve the same purpose as they did in

Final Fantasy VII: they help the player move through the game and devour the story at a faster pace. There's a kind of satisfaction in finally getting through a dungeon and beating a boss, in earning the right to advance after an hour or two of harvesting enemies for gold and experience points. But it's also kind of insulting to be told your numbers aren't high enough to earn admittance to the next area of the game or the next chapter of the story. Itoi is more of a classic writer/storyteller than a full-blooded game developer; now that the RPG has crawled out from the primordial ooze of the 1980s from whence

Ultima and

Dragon Quest were formed, he sees no reason to let the stat numbers and equipment and enemy encounters exert more ohms against the current of the plot more than is necessary.

Right. The plot.

MOTHER and

EarthBound both place their emphases on exploration, but

MOTHER 3 is largely plot-driven. Although we could try to write up a list of characteristics that define an RPG as exploration-driven (like, say,

Dragon Warrior or

Final Fantasy I) or plot-driven (like

Final Fantasy IV), it might all be arbitrary. We'd beginning with a premise of misattribution; it would be like people discussing the particulars of piano tuning while believing that the sounds emerge from its keys rather than its strings. The motive force of any RPG, any game, is the player's thumb on the joystick. In any RPG, you guide your little in-game avatar through the environment of the game until you reach some obstacle that prevents you from proceeding any further. You poke around the area already open to you until you find a means of surmounting the obstacle, and you proceed into the new area until you come across some other obstacle, and you repeat this until the game tells you congratulations, you've made it to the end.

Maybe the fundamental difference is this: are you pressing your thumb to the joystick because you want to see what lies ahead, or because you want to see what happens next?

Of course, we could just as easily equate one to the other. Maybe the only difference is the amount of time one spends hitting the "confirm" button while watching the characters in the game talk to each other. And you do a

lot of this in

MOTHER 3 compared to

EarthBound.

EarthBound has a lot of text, sure, but most of the people Ness meets just stand still and deliver monologues to him. "Cutscenes" abound in

MOTHER 3. You'll frequently sit and observe conversations between two or more characters, and they're rarely standing still while they speak. They gesticulate, they pace, they run through situtionally unique animations. This is as new for the

MOTHER series as it was for

Final Fantasy in 1991. It makes for a very different kind of trip than

EarthBound; but

MOTHER 3 aims at a totally different target, and uses a different toolkit to hit it.

If

MOTHER and

EarthBound are both fairly uncomplicated mutations of the Hero's Journey of myths and epics,

MOTHER 3 might be more like a post-1900 novel. The basic outline of the picture is mostly extant: there's the summons to adventure, the journey outside the world of the familar and the sequence of trials therein, the acquisition of special treasures and powers, the battle with the archvillain and the restoration of the world—but now it's become more layered, more nuanced, more complicated. Many more perspectives are involved than before, and some degree of ambivalence has crept in. What's more, the size of the stage has shrunk, and so the show is a much more intimate proceeding than its Broadway-sized predecessors.

This might not have been the case for

EarthBound 64, had it come to fruition. In

a long 2006 interview with Nintendo Dream Magzine (translated by Tomato, of course), Itoi and his interviewer discuss how

MOTHER 3 ended up being a lot less dark than was called for by the blueprints to its cancelled prototpye:

[Interviewer:] So why did the GBA version end up with the lightened scenario?

Itoi: (pauses to think)... I guess I became a good person.

[Interviewer:] (laughs)

[Interviewer:] Did your loyal MOTHER fans have any influence in your becoming a "good person"?

Itoi: Not at all. I can profess right now that I haven't been changed by the fans. If that were the case, then Yujiro Ishihara and Ken Takakura would be different people now, because of me. (laughs) I am grateful for the messages from my fans. It makes me happy, but it's certainly not like that's all it takes to change a person. It's not like that. You can't just make it so you're influenced by people.

[Interviewer:] Well that's a bit rude!

[Interviewer:] Well that's a bit rude!

Itoi: No, no. The big thing here is the group of people around me. Like if an employee gets married or something.

[Interviewer:] I see.

Itoi: When we made MOTHER 2, there were practically no married men with us at all. People who are involved with the development of a game are like a group full of weirdos, infecting the air with this pretentious attitude that blashphemes anyone who wouldn't look forward to all-nighters [on the project]. Gaming magazines are the same way. (laughs)

[Interviewer:] The editing department is crawling with singles. (laughs)

Itoi: As if to say, "If you're looking for a normal sense of happiness, you're better off going to a respectable company!" (laughs) There was a time when thinking stuff like that gave a person a solid feeling of pride. Same as someone boasting, "Man, I smoked too many cigarettes and I feel sick now."

[Interviewer:] (laughs)

[Interviewer:] (laughs)

Itoi: But looking at it now, I see for example how happy I am if a co-worker has a child, and how truly sad I feel when an employee falls ill. So it's like I have literally become a father, myself. So if I put up some pretense and die from it, I've got nothing to show for it. I can't do my job well if I'm too busy coughing from cigarettes. (laughs)

EarthBound was about exploring huge a new videogame world, and to some extent, about examining the experience of exploring a video game world.

MOTHER 3, ten years removed from

EarthBound, is primarily concerned with

people.

With that in mind, let's begin our customary survey of the game's

PEOPLE & PLACES

NOWHERE ISLANDS

The first two

MOTHER games were set in fictional fascimilies of late 1980s and early 1990s North America. This was one of the series' gimmicks from its inception: while other console RPGs took you to medieval fantasy and/or high-tech sci-fi worlds,

MOTHER remained on Planet Earth in the twentieth century, and was hardly any less fantastic or strange for it.

MOTHER 3 mixes things up a bit. From the onset, all we know is that its events occur in a place called the Nowhere Islands. The location of the islands in space (Earth) and time (the distant future) are kept secret until the final hours of the game.

What's more interesting to me than Itoi's removing the series from a recognizable modern-day Earth and into a fantasy setting is the relative smallness of the new venue.

It's a reversal of what we see in RPG series like (oh, which to choose)

Final Fantasy. The original

Final Fantasy's world map was huge for 1987, but over three console generations it was successively dwarfed by the twin planets of 1992's

Final Fantasy V, the vast and varied world of Gaia in 2000's

Final Fantasy IX, and the repulsively titanic Ivalice of 2006's

Final Fantasy XII. MOTHER, meanwhile, appears to have been shrinking.

MOTHER's Rural America, as we've already seen, was defined by sprawling open spaces and long, dangerous paths between its towns. There's probably no practical way of comparing the number total of traversible tiles in each game, but

EarthBound often

feels smaller than

MOTHER, since it does away with so much of that blank space. And compared to

EarthBound, MOTHER 3 seems teeny-tiny. Again, I'm not about to open up all the maps of all three games and take their measurements, but I wouldn't be the least surprised to find that

MOTHER 3's dimensions are the smallest.

To illustrate the series' shrinking act, let's compare some maps.

From

MOTHER: Yucca Desert

From

EarthBound: Dusty Dunes Desert

From

MOTHER 3: Death Desert

From

MOTHER: Snowman

From

EarthBound: Winters

From

MOTHER 3: Snowcap Mountain

From

MOTHER: Mount Itoi Plateau

From

EarthBound: Peaceful Rest Valley

From

MOTHER 3: Drago Plateau

The Nowhere Islands are just about as varied as Eagleland and its neighboring countries, featuring all the requisite console RPG backdrops. You have the graveyard, the haunted house, the volanic caves, the snow fields, the desert, the jungle, the high-tech dungeon, the mountain path, the underground maze, the sewers, etc. They're just a lot smaller—and, for the most part, much richer.

EarthBound traded the sweeping open spaces of

MOTHER for smaller, more detailed environments, and

MOTHER 3 follows suit, shrinking the maps even further, but making more intentional use of its spaces.

Is this an instance of streamlining of of dumbing down? The answer probably depends on how you like your RPGs. But it's an apt change for a game that's taken a different aim than its predecessors.

MOTHER and

EarthBound were adventure stories about a boy setting out from home to find out where the horizon ends, and a hero must have a suitably expansive world to explore.

MOTHER 3, however, is largely a drama about a family and the community to which it belongs, and so the dimensions of the stage must be commeansurately smaller.

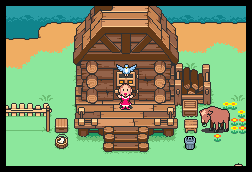

TAZMILY VILLAGE

A familiar trope in console RPGs: a person of uncommon talent and potential is galvanized by the call to adventure and sets out from his remote little village into rolling vistas of the unknown, where fantastic trials and transformations await him. Leaving home, the demense of the familiar, is necessarily the first step. In more traditional and linear media, it's often the case that the hero of an adventure story doesn't cross back into the presincts of his community until his journey is concluded, his tests overcome, his ogres vanquished.

But video game heroes usually enjoy more flexibility and mobility. RPG heroes might have the means to return home, but there usually isn't much point in taking them there. You can guide your RPG crew back to their old stomping grounds, but the people they speak to will usually tell them precisely the same thing they did when seeing them off five or ten game hours ago, and the weapon and armor shops are still peddling the same rusty, obsolesced wares. It's often as though the town becomes frozen in time at the moment of the hero's departure.

For the most part,

EarthBound is no exception to this. Between Ness's egress from Onett and his return after his apotheosis in the Fire Spring (when Onett

has changed), he has only one (1) occasion to return to his hometown on a small errand to retrieve a library book. Onett is in Ness's rear miror for the greater part of his adventure, and most of its people become irrelevant as soon as he setttles his business with the Onett Police Department and moves on.

But the heroes of

MOTHER 3 never stray far from Tazmily. And for as long as we see Tazmily, it's never quite the same place from one day to the next.

Tazmily is unusual for a console RPG hometown. Most RPG heroes' home villages are populated by nameless people with generic character sprites. Though it might be the case that the hero has known the villagers for his entire life, the game will treat them as a bunch of nobodies. Who are these people? What do they do? Who cares? It isn't important.

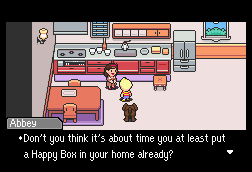

Each of Tazmily's 43 residents (if I'm counting correctly) has a name and their own unique sprite, and their place in the community is usually made clear. Lighter is a lumberjack; he is assisted by Bud and Lou, he has a son named Fuel, and he's close friends with Flint. Bronson is the blacksmith and apparently the de facto constable. Jackie and Betsy oversee things at the Yado inn and tavern, and their employee Tessie also serves as a nurse. Abbey the florist is married to Abbot. Thomas runs the bazaar; his wife is Lisa (a close friend of Hinawa), and their children are Nichol and Richie. Caroline is a baker; Angie is her daughter. And so on. And you can't but get acquainted with them all in the first half-hour of

MOTHER 3: almost everyone pitches in to help look for Hinawa and the kids, and most of them turn out for the funeral the following day.

When we first step into Tazmily, it seems like the podunk of podunks: it's tiny, it's situated literally in the middle of Nowhere, and it doesn't have access to anything but the most basic comforts: virtually every structure in town is constructed from lumber, the houses are lit by candles and lanterns, and there's no electricity or running water. It's a peaceful, stable place, and as far as we can tell, the villagers enjoyed it this way. We have to use "enjoy" in the past tense, since we never get to see what life in Tazmily was really like before the Pigmasks start in.

Three years after Hinawa's death and the arrival of Fassad and the Pigmasks, Tazmily is a very different place. In the wake of its rapid modernization, we find paved roads, houses with electricity and all the modern amenities, and a burgeoning population. We're introduced to the same Tazmily at the same time we take control of Lucas, who now looks much more similar in stature to Ness. So at the same time that we take control of a character who looks like the hero of

EarthBound, we find ourselves in a place that suddenly looks a lot like Onett. It's a clever trick: the nostalgic

EarthBound fan will be inclined to be overjoyed, but it's hard for her not to experience some cognitive dissonance when she knows that the drivers of these changes are following a sinister agenda that probably doesn't have the best interests of the villagers in mind.

It's odd, though: the Tazmily scenario becomes inversion of the usual Trouble in River City trope of the console RPG. You know how it goes: the hero is spurred to action because his hometown is plagued by some inimical outside agency. Examples off the top of my head: Guardiana in

Shining Force is invaded by the marauding hordes of Runefaust. Rabanastre in

Final Fantasy XII is under occupation by the oppressive Archadian Empire. Roccoco in

Robotrek suffers from the machinations of the Hacker gang.

Grandia II's Carbo village is beset by nocturnal terrors. Strange things are happening around Podunk and Onett in

MOTHER and

EarthBound as a malign alien influence takes root. But in

MOTHER 3, the darkness that descends upon Tazmily Village is...uh, technological improvement and material prosperity. While almost everyone in town tells Lucas how much better off they are now than they were three years ago, our hero finds himself compelled to work against and subvert his village's benefactors. Huh.

Although the Tazmilities are seduced by Fassad's missionism and invite the Pigmask Army into their town, they never really become

evil people. Abbot and Abbey become born-again consumer whores and treat Lucas with condescension for not keeping pace with the times, but when we last see them they're looking out over the city lights and talking about their love and devotion to one another. This is the sort of ambivalence that haunts

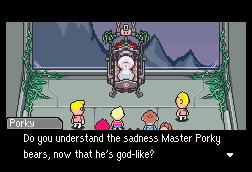

MOTHER 3—a story of decent people who are prone to misdirection, strong-hearted but flawed heroes, cruel men who do kind things, and malevolent demons deserving of pity.

HINAWA

EarthBound

EarthBound began the same way as

MOTHER, and

MOTHER 3 begins the same way as

EarthBound: by asking you to assign names to a few people, and then to name Your Favorite Food and Your Favorite Thing. In the first two games, the characters being named stand against the backdrop of a menu screen, and their future relationships as travelling companions is implied only by the fact that you're being asked to name them in the first place.

MOTHER 3 departs from its antecedants by placing the conventional naming screen windows in front of a house, and showing the characters in question interacting with each other. Even before any actual narration begins, we're aware that the people we're looking at and christening comprise a family with two parents, a pair of twin sons, and a dog.

If you go by the default names, you get Flint, Hinawa, Claus, Lucas, and Boney. The husband/father Flint is the player character in Chapter 1. The younger twin Lucas takes the wheel from Chapters 4 through 8. Boney is party member in six of the eight chapters, and there's a moment in the prologue when Claus joins Lucas in a joke tutorial battle against a rambunctious mole cricket lookin' to wrassle. The only family member who's never a usuable character is Hinawa, the beloved wife and mother.

Until now, the title

"MOTHER" has always possessed some kind of abstract or oblique significance with regard to the game it represents. Itoi's first game was named after a John Lennon song: he was struck by the rawness and the conflicting emotions with which the word was sung in refrain after refrain, and it comes to refer to Giygas's irreconciliable but mutually persistent loathing of humanity and love for Maria. In

EarthBound (ahem,

MOTHER 2), the word probably refers to the Earth itself. We don't need to look very deeply to see the word's meaning in

MOTHER 3: it refers to Hinawa. And that's why we'll start with her. She is, in a manner of speaking, the titual character.

We never learn much more about Hinawa beyond what's inscribed on her gravestone:

Wife of Flint.

Mother of the twins Claus and Lucas.

Daughter of Alec.

May the beautiful Hinawa rest in peace here for all time. Perhaps it doesn't say very much about the personality of the woman herself, but nothing exists but in relation, and this is especially true in such a small and mutually interdependent community like Tazmily. It's probably enough to say that Hinawa is presented as the angelic ideal of the nurturing, protective, self-sacrificing wife and mother, and for the purposes of this narrative, she doesn't need to be a Molly Bloom. She's considered almost entirely in retrospect, and through the actions and recollections of her grieving husband and children. ("Real love," Tony Kushner writes, "is never ambivalent.")

Like

The Sound and the Fury, MOTHER 3 has at the center of its family drama the empty space left behind by the woman who isn't there. Hinawa dies half an hour or so into the game. She's barely seen onscreen and hardly gets any lines, but her absence is felt throughout the entire game. Almost every action undertaken by Flint, Claus, and Lucas is, in one way or another, in response to her death. (The entirety of Chapter 6 consists of Lucas literally chasing her ghost.)

Back to the naming screen:

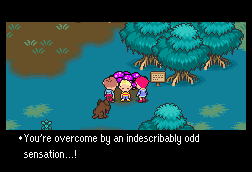

MOTHER 3 uses the now-familiar "what's your favorite food?" prompt to play a mean trick on veteran players who go into the game thinking they know what to expect. In the first two games, you could always count on being able to walk or warp back home, where you could talk to Mom and let her serve up a heaping plate of Your Favorite Food for some cost-free HP/PP recovery. This never happens in

MOTHER 3. The only time we see Lucas enjoying the flavor and magical healing properties of Your Favorite Food is during the prologue, when he sits down with Hinawa and Claus for what will be their final meal together. Throughout the game, Your Favorite Food is sporadically mentioned, but only as a tease: you won't find it in any store, it's not sold in any vending machines, and Lucas will always return home to an empty house with an unset table.

CLAUS

As long as we're making spurious analogies to

The Sound and the Fury, why don't we go ahead and and point out the areas of overlap between Claus and Quentin Compson? They're the lost sons and brothers; both go off and do something crazy and suicidal for the sake of the missing woman in their respective stories. Quentin is so haunted by his memories of his sister Caddy, so utterly lost in both his family and the world without her, and so pounded into self-hatred and despair by the discrepancies between the chauvenistic ideals of the moribund culture he's been made to internalize and the sordid realities of life, that he throws himself into the Charles River and drowns himself. Actually, Quentin's story is pretty complicated, but Claus's motivations are much simpler: a Drago (an ordinarily friendly kind of Tyrannousaurus indigenous to the Nowhere Islands) that's been chimerized and corrputed by the Pigmasks kills his mother, and he runs off into the hills by himself with his dad's knife, bent on a retribution killing. He's never seen alive in Tazmily again.

From what we know of Claus, he seems much more similar to

EarthBound's Ness than Lucas does. None of the kids in Onett ever stop yapping about how strong and brave and cool Ness is, while Claus is the headstrong, adventurous yang to Lucas's timid, lachrymose yin. And on the face of it, the beginning of Claus's story is a lot like Ness's, too: when his family and their hometown are beset by paranormal forces, he immediately sets out from home on a mission, armed only with a household implement and some psychic powers he picks up during the first leg of his journey. (Lucas's adventure in Chapter 4 begins much more haphazardly, and with much less dramatic flourish.) But unlike Ness (or Lucas, for that matter), Claus has the misfortune of receiving a crippling injury that prevents him from fulfilling his goal or returning home, and Destiny hasn't allotted him a retry screen in the event of such a disaster.

This isn't the end of Claus's story, of course, but we'll come back to him later.

FLINT

How's this for an inversion of expectations: after two

MOTHER games where the young hero's father is never seen in person,

MOTHER 3's version of "Dad" not only has a proper name, not only appears in the flesh, but is actually the player character during the first chapter.

Flint looks like a cowboy, but he actually tends sheep. What else do we know about Flint? Not much, really. We're told in the naming screen that he's a strong, kind, dependable father. It's not much, but it's all we get. He goes mute as soon as the character takes control of him at the beginning of Chapter 1. Afterwards, he becomes an NPC for the remainder of

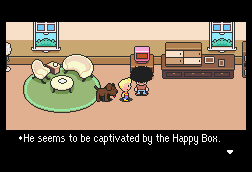

MOTHER 3, and it seems he's not quite the same man he was before. "Kind" and "dependable" aren't words that describe the Flint we see after Hinawa dies (the surprising emotional rawness of the scene where he gets the news should be taken as an admonition by anyone in the business of writing video game narratives) and Claus goes missing. Three years after the arrival of the Pigmasks, all he does is wander up in the hills, searching for Claus. Sometimes he comes back for a few minutes to lay a fresh boquet of flowers on his wife's grave. We might have to assume that he's also coming back every now and then to rebuild the old ranch whenever it gets struck by the Pigmasks' lightning. It's a wonder he actually bothers: the only person who spends any time at home is Lucas, who's clearly on the outmost periphery of Flint's concerns.

The irony of finally having a human father instead of a voice on the phone in a

MOTHER game is that Flint becomes even more distant from Lucas than "Dad" was from Ness in

EarthBound. Dad is always just a phone call away, and unless you're playing on an emulator and using savestates, you'll be talking to him frequently. Except for the very beginning and very end of

MOTHER 3, Flint is almost as absent a figure in Lucas's life as his dead mother and vanished brother.

For all of

MOTHER 3's quirkiness, all of its talking mole crickets and carousing ghosts and magical drag queens and absurd chimerical animals, it can't be overlooked that it's basically a story about a broken family. (Just like

The Sound and the Fury! Give me a break, I love that book.)

There are two wonderful moments involving Flint at the end of the game that are deserving of mention. The first is when Flint goes off ahead into the "Cave of the Future." As Lucas catches up, he find his father's hat drifting through the air and disappearing over the abyss. Further ahead, we find Flint. The camera pans to show a hatless (and bald) Flint by himself on his hands and knees, looking utterly old and broken and alone. It's an important moment; it plainly shows the completeness of Flint's desolation at that point, but it's also very brief, uncomplicated, and untheatrical.

As Lucas and Boney crouch over him, he says to Lucas (without turning around to look at him): "that masked man...He's Claus. Lucas... He's your brother... Claus. [...] As a father, I've finally found the son I lost. Lucas. Be happy. I've finally, finally found your brother." He ends there, and says nothing further unless you approach and

speak to him again.

*

How are we supposed to feel about this? How should

Lucas feel about it?

Should he be happy? After all, Lucas never seemed to share his father's morbid obsession with finding Claus. Does Flint's belated success do anything to cancel out the three years of paternal negligence to which he subjected the son who was still with him? Who knows? When I said earlier that

MOTHER 3 is more infixed with ambiguity than

MOTHER or

EarthBound, this is exactly the sort of thing I was talking about.

At any rate: Flint is not only a character in the story, he's also your sole party member for most of Chapter 1. Though he's incapable of psychic attacks, his Brute Force abilites let him power himself up, hit all enemies at once with a physical attack, or sacrifice accuracy for increased power. As such a straightforward physical fighter, he's an evolved (and less boring) version of Teddy from

MOTHER.

*I'm betting Itoi hid Flint's remarks to Lucas about his glabrous noggin behind as many repetitions of the same line because they rather detract from the gravity of the moment. But it's nice that the speech is there if you look for it, and such are the advantages of a nonlinear medium.

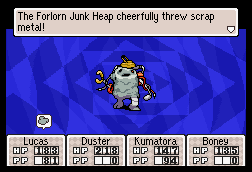

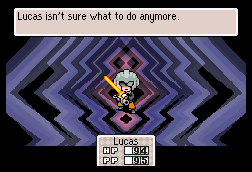

LUCAS

Ah. Here we are. Ness—savior of the universe in

EarthBound, the bravest, strongest, most bad assed boy in the world—is succeeded in

MOTHER 3 by Tazmily Village's resident weakling and crybaby. Ness has what it takes to go off on a quest to save the Earth from the very beginning of his story; Lucas doesn't even demonstrate his latent moxy until the end of Chapter 3, and then has to wait another three years before destiny comes a-knocking again at the beginning of Chapter 4.

Actually, Lucas is a lot less like Ness and a lot more like

Final Fantasy Tactics' Ramza, the coddled, privileged runt of a military cadet who takes a stand against the whole fucking world. Lucas is a blonde-haired late bloomer of an RPG protagonist, sure, but he shares two specific traits with Mr. Belouve. The first is that he's a kind and thoroughly decent kid who is able to win allies to his side. The most important case in point are the Dragos: when Hinawa is killed by a modified Drago, Claus responds by going out and trying to kill it. (His dialogue might even imply that he wants to kill

all the Dragos, but we could be reading too much into it.) When Flint sets out to find Claus, he comes across the Drago that killed Hinawa and mortally wounds it, angering its child. And then it's Lucas who goes out, finds the remaining Dragos, reconciles with them, and brings them to Duster and Kumatora's aid when they're cornered by Fassad and a squad of Pigmask soldiers.

Secondly: like Ramza (and unlike Ness), Lucas is a pariah. His situation might not be as grim as Ramza's (branded as heretic, traitor, and anarchist), but three years after Fassad and the Pigmasks arrive, he's become a persona non grata around Tazmily. He's the son of that whackjob Flint, after all—an outlier to be regarded with suspicion or condescension, or to be avoided altogether. Lucas's first mission is to search for the missing Duster, whom none of the other villagers are interested in finding, and to foil a villain seen by the rest of Tazmily sees as a friend and benefactor. When his status as the "the chosen boy" becomes clear, Lucas is subsequently tasked with seeking out and pulling the Seven Needles to awaken the Dark Dragon sleeping beneath the Nowhere Islands, which could well mean the end of Tazmily. It's all very true to life: doing what's right often doesn't make you popular.

Even if we were to conclude that

MOTHER 3 has been dumbed down as an RPG (and we're not), we'd still have to give it credit for doing a much better job at balancing the attributes of its player characters then either

MOTHER or

EarthBound. Lucas, as you might expect, handles a lot like Ness in battle, but with some notable differences. He's still the strongest physical attacker, he still inflicts negative status effects with PK Flash, he still serves as a healbot with all four versions of PK Lifeup, and he still commands the nuclear option with the pricey but unparalleled PK [Your Favorite Thing]. But now he's also become the team's assigned bufferizer—and given how much stronger

MOTHER 3's bosses are than

EarthBound's, your crew needs every edge it can get. But he's no longer the one with the most HP or PP, and now he's also

slowest party member, always taking his turn last.

MOTHER 3 still uses

EarthBound's rolling HP bars, which means there's always a chance that PK Lifeup Omega might come out too late.

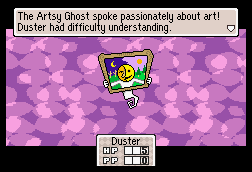

DUSTER

Think for a moment: what's one thing that nine out of ten JRPG goodguys have in common? Aside from an unusual resilence to planet-consuming cosmic explosions and gunfire, I mean. And also aside from the innate ability to pilot any given land, air, or seafaring vehicle, now matter how advanced or alien its engineering might be. And apart from being ineffective at sniffing out the obvious subterfuges of obvious villains.

Answer: they're all attractive and well groomed! With the exception of the occasional "old man" stereotype or "freak" party member, just about every character in every modern Japanese RPG has the type of face that would perform quite admirably on Tinder, and dresses with a conscientious (though not always well-advised) sense of style.

And that's why I'm so fond of Duster, Tazmily's resident gentleman of the shade. He's a JRPG hero with a horse face. And he's shabbily dressed and poorly groomed, and he's got bad breath, a big wart or mole on his face, and an ill-advised mustache.

And he walks with a steep limp because of a bum leg.

(It's funny: most of the people drawing

MOTHER 3 fan art seem incapable of accepting this. Their renditions of Duster frequently diverge from his in-game appearance, shrinking his nose, smoothing out the shape of his head, styling his hair, and so on.)

And I like Duster even more because he had to win me over. Seeing him the the early screenshots of

MOTHER 3, I reacted like any orthodox fanboy: "WHO THE HELL IS THIS AND WHY ISN'T HE A LOID/JEFF CLONE?" Fifteen minutes into Chapter 2, where Duster Indiana Joneses his way through the haunted Osohe Castle in search of the mysterious Hummingbird Egg relic,

EarthBound somehow seemed poorer for not having a muttonchopped shinobi of its own. Acquired tastes are the ones we savor most, after all.

Duster is a new sort of party member in the

MOTHER series. Loid was a geek with a talent for gadgeteering who could occasionally come in handy when you figured out what items to put in his hands, knew where to find them, and went to the trouble of collecting them. His successor Jeff could be tremendously, game-borkingly powerful if you figured out what items to put in his hands, and they really weren't that hard to find. So

MOTHER 3 starts from scratch, replacing the engineer-type character with that tried and true RPG staple, the thief. But Duster doesn't steal—instead he packs six reusable Thief Tools (which sit in the Key Items box, keeping his inventory uncluttered) that inflict negative status effects and debuffs on individual enemies at no cost. Neat! He's also the second strongest and second fastest character, and he's got the most HP. Neat! And he occasionally acts at the start of battle, getting in a random first hit before the command window appears, or reverses the situation when an enemy surprises the team from behind. Neat! (It was because of Duster that I learned that hitting an Atomic Power Robot when its back is turned disarms its self-destruct device. Nice touch. And also neat!)

KUMATORA

When we looked at

EarthBound, we compared Paula to Ana, her predecessor in

MOTHER. Now: let's compare and contrast Paula with

Kumatora, MOTHER 3's heroine.

Paula is an ingenue sweetie pie raised by a waspy couple who own a preschool. Kumatora is a tomboy punk raised by a tribe of immortal transvestites/-sexuals/-somethings. Paula hits enemies with a frying pan because she's a girl. Kumatora attacks enemies with her fists because she's had enough of their shit. Paula fries the opposition with deadly elemental psychokinesis. Kumatora fries the opposition with deadly elemental psychokinesis. Paula wears a modest pink dress and ties bows in her blonde hair. Kumatora wears a hoodie and lets her pink hair do whatever it wants.

Paula is sweet and polite. Kumatora is brash and brusque. Paula sits in a cell with her teddy bear and waits for Ness to come rescue her. Kumatora gets caught in a beartrap is about to cut her foot off when Wess and Duster happen upon her. Paula falls in love with Ness. Kumatora doesn't show much interest in either of her male party members. Paula might be named after pop music footnote Paula Abdul. Kumatora's name literally means "beartiger" in Japanese. Paula prays. Kumatora curses.

Told you before I was more of a Kumatora fan. Still, it would have been nice if one of Itoi's female characters got her own extended chapter in one of his games.

As a party member, Kumatora is par for the course. She alternates with Boney as the group's weakest physical attacker (her base stat is lower, but she enjoys more frequent equipment upgrades), and has the second-lowest HP and speed, but she's the only party member other than Lucas to wield PSI, and her PP is usually higher than his. Her psychic aresenal is something like a conflation of Paula's and Poo's: she gets all the offensive elemental PSI in addition to debuffs, status afflictors, some basic recovery techs, and PK Starstorm. Protip: if Kumatora learns PK Ground, you're definitely overleveled.

Interesting: like the enemies of

EarthBound (and most other RPGs), most of

MOTHER 3's baddies are variously resistant against and susceptible to fire, ice, and lightning elemental attacks. But this time around, Kumatora is pretty much the only character to whom these attributes have any relevance. Would you call this streamlining or of dumbing down?

BONEY

We've already discussed the ungainliness of fourth characters in our overview of

EarthBound—they're problematic in that they're too often just one superfluous figure added to the magical triangle.

MOTHER's fourth man was Teddy, the boring gang leader.

EarthBound's fourth man was Poo, the incongruous and redundant karate prince.

MOTHER 3's fourth man is Boney, the wonder dog. Unlike Teddy and Poo, Boney never seems like an afterthought, as he's with Flint at the very beginning and immediately joins Lucas at the start of Chapter 4. Perhaps he helps keep the special Hero/Buddy/Girl triad intact because he and Lucas count as a single conjoined character—sort of like Dorothy and Toto.

Boney's only antecedent in the series is King, who joins Ness to look for Picky on the night the meteor crashes up in the hills. King is reluctant to go out to begin with; he chickens out and runs home before he even gets to the top of the hill (and to be even more of a wimp than Pokey takes some work), and for the rest of the game he just mopes indoors and refuses to go out. King is really kind of a shitty dog.

But Boney is the superpet superpal an RPG hero deserves. Unlike King, Boney doesn't need to be coaxed into helping out: if Flint or Lucas try walking past him, Boney will run up and demand to be taken along, and won't take no for an answer. At the beginning of Chapter 4, Lucas is alone—his mom is dead, his dad is never around, his brother is long gone, and the people of Tazmily distrust him—but he can still trust Boney to be at his side. Boney is the perfect dog, steadfast in his loyalty and willingness to take care of the family he loves. He melts my heart.

In battle, Boney might not seem to have much going for him. His special ability lets him sniffasniffasniff an enemy to learn its weaknesses—which isn't really that special, since it's usually easy enough to guess. He has the least HP, and he's not the strongest attacker. But unless he's significantly underleveled, Boney's high speed stat makes him consistently the first party member to act during a given round in battle. He's the one you load up with HP recovery and status-curing items to save your crew from rolling down to zero, and make sure an ally's status effects are cured before his or her turn comes up. (He's also the one you give the Shield Snatcher to if you're lucky enough to find it.) Boney's his combos are also the most fun to listen to, and that counts for more than you might think. (Some players have suggested that his sharp, discrete notes actually make his combos the easiest to perform. Maybe that's the reason why I tend to score more hits with him than anyone else?)

SALSA

I had to do a lot of thinking to figure out just why Salsa the dancing monkey is actually in

MOTHER 3 at all. He's the player character during Chapter 3, and then disappears until he's needed to open a door in Chapter 7. For the rest of the game, he doesn't do much of anything else. He's not much fun to play as: his damage output is pitful, his Monkey Tricks are mildly amusing rather than useful, and Fassad does most of the actual work in battle. His "deliver four boxes to four select villagers in under twenty-three minutes" mini-game (and we use the word "game" very loosely) could be Figure 1 in the dictionary entry for "RPG busywork," although I guess being made to feel enslaved is nothing if not "immersive."

So why turn a whole chapter over to Salsa? Pure chutzpah, maybe: to the best of my knowledge, no other RPG has ever had the imagination or the balls to put players in the role of a monkey held captive by a mephistophelean huckster who tortures him and forces him to dance. But more practically, it's an effective means of providing exposition for Fassad and the Pigmasks from the embedded perspective of a hostage who's seen what they're up to and can't tell anybody about it (except for the psychic Kumatora). That makes Salsa a cute little plot contrivance: we need to know that Fassad feels nothing but contempt for the people of Tazmily, and there also needs to be a good reason for Kumatora, Wess, and Lucas to run afoul of him and see him when he's not putting on his benignant act for the townsfolk. (It might also be that having a third new player character in as many game chapters is a clever, subtle means of conveying the extent to which the Pigmasks' arrival has destabilized the Nowhere Islands: things have become so unsettled that not even the main character of the game can remain consistent for more than a couple of hours at a time.)

THE MAGYPSIES

Want to know why

MOTHER 3 ain't never getting an official North American release? This might be at least part of the answer.

Late in

MOTHER 3, Lucas is dispatched on a lengthy "find the seven plot tokens" quest. Two unusual things about this: one is the timing. Ninten and Ness were both implicitly or explicitly given their "find the Eight Melodies" assignments at the very beginning of their games, and they spend most of their respective adventures tracking them down. It's not until Chapter 7 of

MOTHER 3 that Lucas is tasked with his own RPG scavenger hunt, and it's compartmentalized into its own chapter rather than being suffused throughout the whole affair. What's more, MOTHER 3 diverges from the old script by eschewing musical notes as the object of the quest. This time, our hero has to locate and pull out the Seven Needles stuck into the pressure points of a colossal dragon sleeping beneath the Nowhere Islands.

Each of these needles is attended by an ageless, magical maiden named after one of the Greek musical modes: there's Aeolia, Doria, Lydia, Phrygia, Mixolydia, Ionia, and Locria. They're also natural PSI users, and were the ones who awakened the latent powers in Claus, Lucas, and Kumatora. So far, so good.

Also, each of these maidens is also a dude. Kind of.

It's a reversal of what we usually think of "androgyny." Usually the term evokes a personal aesthetic in which the more salient aspects of both sexes (and their typically associated genders) are dampened, resulting a person who might seem vaguely masculine, but somewhat feminine as well. The Magypsies, on the other hand, are extremely masculine and extremely feminine at once. Their voices are indescribably deep, yet shrill. They have visible stubble and the hard outlines of male faces, but they mince about like debuntantes. And they...

It's a reversal of what we usually think of "androgyny." Usually the term evokes a personal aesthetic in which the more salient aspects of both sexes (and their typically associated genders) are dampened, resulting a person who might seem vaguely masculine, but somewhat feminine as well. The Magypsies, on the other hand, are extremely masculine and extremely feminine at once. Their voices are indescribably deep, yet shrill. They have visible stubble and the hard outlines of male faces, but they mince about like debuntantes. And they...

Actually, the Magypsies are just a great big mishmash of gay crossdresser stereotypes. One gets the sense that they'll go down in video game history the way the crows from Dumbo are remembered by animation historians who apologize and shake their heads. But heck: it's hard not to like the crows in spite of everything, and I doubt you'll find many MOTHER 3 players who weren't won over by the Magypsies. And everyone in the world of MOTHER 3 likes them too. Nobody says they're not strange—that's readily admitted—but people seem more impressed by their kindness, wisdom, and beauty. "Delight is to him," says Herman Melville, "who ever stands forth his own inexorable self," and the Magypsies are never anything but delighted to let their freak flags fly.

This time through MOTHER 3, I was less interested in the Magypsies' genderingbendering strangeness than in their attitudes towards mortality. When they speak to Alec and Flint in Chapter 1, they have a flippant, almost disdainful attitude towards human life. What concern is a human lifespan to someone who's lived thousands of years, and expects to live for at least a few thousand more?

This time through MOTHER 3, I was less interested in the Magypsies' genderingbendering strangeness than in their attitudes towards mortality. When they speak to Alec and Flint in Chapter 1, they have a flippant, almost disdainful attitude towards human life. What concern is a human lifespan to someone who's lived thousands of years, and expects to live for at least a few thousand more?

But when the Needles they protect are pulled, the Magypsies disappear. This means that once the Masked Man begins removing the needles and gets the process underway, the Magypsies must be erased from existence, one by one. Maybe they're entitled to be a little condescending towards human attitudes about death, since each of them (except maybe for Locria, but that's another discussion entirely) is the very model of grace and humility when her own number is called. Only in a MOTHER game would one expect to find such a marriage of frivolity and wisdom.

DCMC

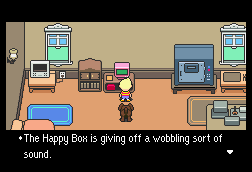

Happy Boxes aren't the only form of decompression enjoyed by Tazmily's working stiffs a long day of grinding labor at the Clay mines. The factory workers all get free passes to Club Titiboo, where they can suck down booze, enjoy the attention of cute cabaret girls, and watch live performances by DCMC (Desperado Crash Mambo Combo), the hottest band on the Nowhere Islands. And what are the DCMC's songs about? Why, King Porky, of course!

Happy Boxes aren't the only form of decompression enjoyed by Tazmily's working stiffs a long day of grinding labor at the Clay mines. The factory workers all get free passes to Club Titiboo, where they can suck down booze, enjoy the attention of cute cabaret girls, and watch live performances by DCMC (Desperado Crash Mambo Combo), the hottest band on the Nowhere Islands. And what are the DCMC's songs about? Why, King Porky, of course!

The DCMC—composed of OJ, Magic, Baccio, Shimmy Zmizz, and Lucky (actually an amnesiac Duster)—are obviously heirs to EarthBound's Runaway Five. Individually, the members of the DCMC are cool cats who just like to jam and give their audiences a thrill. But they are unwittingly acting in the service of the "regime" by helping to pacify its subjects and glorifying the guy at the top of the Pigmask Army pyramid. It's rather insidious: what's allowed to pass for "subculture" in Porky's kingdom is really just an extension of his mind control program. (Do the phrases "corporate rock" and "pop punk" ring any bells or make your skin crawl?)

DR. ANDONUTS & MR. SATURN

From the beginning, Dr. Andonuts and Mr. Saturn were teased in the EarthBound 64 previews. I don't think any of us were really surprised when they turned up in MOTHER 3. In one sense, they seem like throwbacks made for their own sake: neither Andonuts nor the Saturns refer to events from EarthBound or explain how they ended up on the Nowhere Islands (the Mr. Saturns might have even been there to begin with), and Itoi surely could have come up with another self-interested scientist or village of quirky demihumans. But as the unofficial mascot of the MOTHER series, Mr. Saturn pretty much had to return, and Dr. Andonut's appearance makes sense, though it isn't explained—of course Porky would think to kidnap and coerce the scientist whose work was instrumental in the defeat of Giygas. (I guess it does beg the question as to why he didn't nab Apple Kid as well, but we might be reading too much into things.)

From the beginning, Dr. Andonuts and Mr. Saturn were teased in the EarthBound 64 previews. I don't think any of us were really surprised when they turned up in MOTHER 3. In one sense, they seem like throwbacks made for their own sake: neither Andonuts nor the Saturns refer to events from EarthBound or explain how they ended up on the Nowhere Islands (the Mr. Saturns might have even been there to begin with), and Itoi surely could have come up with another self-interested scientist or village of quirky demihumans. But as the unofficial mascot of the MOTHER series, Mr. Saturn pretty much had to return, and Dr. Andonut's appearance makes sense, though it isn't explained—of course Porky would think to kidnap and coerce the scientist whose work was instrumental in the defeat of Giygas. (I guess it does beg the question as to why he didn't nab Apple Kid as well, but we might be reading too much into things.)

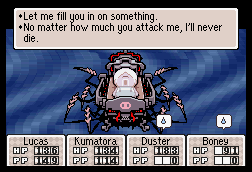

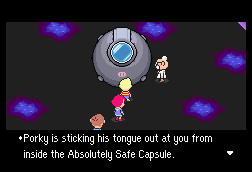

Once again, they fulfill auxilliary roles in the hero's adventure: Dr. Andonuts provides special chimeras to help Lucas reach the second Needle, and a Mr. Saturn polishes the Courage Badge and returns it to Lucas as the Franklin Badge. But in their most important function within MOTHER 3's plot, they mimic their prior roles in EarthBound. When we last saw them, Dr. Andonuts and the Mr. Saturns invent the Phase Distorter, allowing Ness and friends save the world by traveling into the past and confronting Giygas. In MOTHER 3, Dr. Andonuts and Mr. Saturn are compelled by Porky to create the Absolutely Safe Capsule, the ultimate panic room, allowing Lucas and friends to save the world by forcing Porky to retreat into it. (It's funny how "absolute safety" and "absolute imprisonment" basically mean the same thing.)

Once again, they fulfill auxilliary roles in the hero's adventure: Dr. Andonuts provides special chimeras to help Lucas reach the second Needle, and a Mr. Saturn polishes the Courage Badge and returns it to Lucas as the Franklin Badge. But in their most important function within MOTHER 3's plot, they mimic their prior roles in EarthBound. When we last saw them, Dr. Andonuts and the Mr. Saturns invent the Phase Distorter, allowing Ness and friends save the world by traveling into the past and confronting Giygas. In MOTHER 3, Dr. Andonuts and Mr. Saturn are compelled by Porky to create the Absolutely Safe Capsule, the ultimate panic room, allowing Lucas and friends to save the world by forcing Porky to retreat into it. (It's funny how "absolute safety" and "absolute imprisonment" basically mean the same thing.)

(As I type this it finally occurs to me that Dr. Andonuts is first met hiding in a garbage can, just like Loid's father in MOTHER. Two throwbacks for the price of one!)

CHIMERAS

Before meddling with Tazmily's villagers on a face-to-face level (via Fassad), Porky has his Pigmask soldiers initiate the Fascinating Chimera Project: the systematic conversation of Tazmily's run-of-the-mill fauna into belligerent cyborgs and hybrid mutants. And thus we meet one of the largest contingents of baddies Lucas and friends face throughout their adventure.

None of this seems to be integral or even connected to Porky's designs for Tazmily. He just thinks it would be cool. It's the germ logic of the solipsistic engineer, and the essence of the Fascinating Chimera Project: disruptive technology for its own sake. It represents science without conscience run completely amok, and it's an apt metaphor (one of many, really) for an era in which all technological progress is automatically presumed to be beneficial, regardless of its actual ramifications for human life in the long term.

THE PIGMASK ARMY

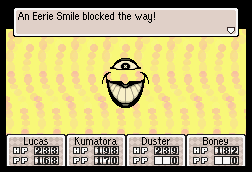

The iconic Starmen, the sleek and menacing alien soldiers of Giygas's army in both previous games, have stepped aside in MOTHER 3 and are replaced by a bunch of fat bastards in porcine stormtrooper outfits. From stars to swine.

The Starmen were elusive foes, usually only found at their outposts and strongholds in the dark corners of the world. The Pigmask incursion begins as a covert operation, but by Chapter 4, they've more or less brought the Nowhere Islands under marial law. They're everywhere. We don't get to see the transition, so it remains unknown how the people of Tazmily are made to consent to their presence. The Happy Boxes' mollifying effect on the populace is obviously a contributing factor. And perhaps the villagers, seeing all the aggressive and strange new creatures running wild outside the village, and suffering from a plague of unnatural lightning storms, turned to the Pigmasks for protection—protection from the very dangers the Pigmasks brought to the island.

The Starmen were elusive foes, usually only found at their outposts and strongholds in the dark corners of the world. The Pigmask incursion begins as a covert operation, but by Chapter 4, they've more or less brought the Nowhere Islands under marial law. They're everywhere. We don't get to see the transition, so it remains unknown how the people of Tazmily are made to consent to their presence. The Happy Boxes' mollifying effect on the populace is obviously a contributing factor. And perhaps the villagers, seeing all the aggressive and strange new creatures running wild outside the village, and suffering from a plague of unnatural lightning storms, turned to the Pigmasks for protection—protection from the very dangers the Pigmasks brought to the island.

How very true to life.

FASSAD

Finally, a MOTHER game finds a persistent antagonist. For most of MOTHER and EarthBound, Giygas's forces lurk in the shadows, unseen except for when the occasional Starman Junior, Mani Mani Statue, or Master Belch puts in an appearance. But in MOTHER 3, the Pigmasks' second-in-4command can be found standing in broad daylight in the center of Tazmily, exposed but frustratingly unassailable. (It's probably understood that Lucas knows it would be suicide picking a fight with Fassad out in the open: even if he was capable of physically threatening Fassad, he'd have an entire legion of Pigmasks dogpiling him in an instant, and the villagers would much sooner turn on him than on their beloved prophet.)

Finally, a MOTHER game finds a persistent antagonist. For most of MOTHER and EarthBound, Giygas's forces lurk in the shadows, unseen except for when the occasional Starman Junior, Mani Mani Statue, or Master Belch puts in an appearance. But in MOTHER 3, the Pigmasks' second-in-4command can be found standing in broad daylight in the center of Tazmily, exposed but frustratingly unassailable. (It's probably understood that Lucas knows it would be suicide picking a fight with Fassad out in the open: even if he was capable of physically threatening Fassad, he'd have an entire legion of Pigmasks dogpiling him in an instant, and the villagers would much sooner turn on him than on their beloved prophet.)

Fassad appears in Tazmily's town square two days after Hinawa's death, acting equally like Harold Hill and a Christian missionary. He promises peaces and happiness to those who listen to his message, and his message is "you need more material possessions and better material possessions." Three years later, most of Tazmily has been inducted into his cult of consumerism. They hang on to his every word, and trust him completely. Nobody in town except for Lucas and Wess have seen him for the sadistic machinator he truly is.

In a way, Fassad is the MOTHER 3 version of the Mani Mani Statue: not only does he serve as an agent of corruption and cause recurring headaches for the heroes, he's also surrounded by more question marks than almost anything else in the game. What was his reason for siding with Porky? Why did he betray the other Magypsies? How would he have felt about having his Needle pulled? Why would he go along with a plan that ends with him disappearing and everything in the world getting killed? Should we imagine that his choice to be rebuilt with trumpets protruding from his face are a sublimation of his Magypsie eccentricities? Why is he in disguise to begin with? What made him decide to be all male and no female? What was he like as Locria? Why don't any of the other Magypsies talk about him? If he's an immortal Magypsie, why does he seem to die after fighting and losing to Lucas and friends in Chapter 8?

In a way, Fassad is the MOTHER 3 version of the Mani Mani Statue: not only does he serve as an agent of corruption and cause recurring headaches for the heroes, he's also surrounded by more question marks than almost anything else in the game. What was his reason for siding with Porky? Why did he betray the other Magypsies? How would he have felt about having his Needle pulled? Why would he go along with a plan that ends with him disappearing and everything in the world getting killed? Should we imagine that his choice to be rebuilt with trumpets protruding from his face are a sublimation of his Magypsie eccentricities? Why is he in disguise to begin with? What made him decide to be all male and no female? What was he like as Locria? Why don't any of the other Magypsies talk about him? If he's an immortal Magypsie, why does he seem to die after fighting and losing to Lucas and friends in Chapter 8?

True to the style of the MOTHER series, none of these mysteries will ever be resolved. And again, sometimes it's more fun to wonder than to know.

At any rate, Fassad might also earn the distinction of being the toughest boss in the MOTHER series. Like most moustache-twirlers, he prefers to let his lackeys do his dirty work for him, but when he's made to exert himself, he means business.

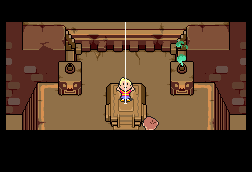

THE MASKED MAN

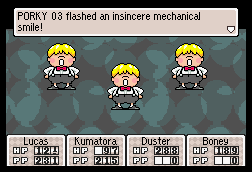

One of the highest-ranking figures in the Pigmask Army is a diminuitive, jackbooted fellow who wears a helmet that obscures his eyes and makes him look like a rebel pilot in a Star Wars flick. Like Lucas, he can use PK [Your Favorite Thing] and pull the Seven Needles. He is so similar in appearance to Lucas that his Pigmask subordinates are occasionally prone to mistaking Lucas for him. When he and Lucas meet face to face, Lucas gets a seriously weird feeling.

One of the highest-ranking figures in the Pigmask Army is a diminuitive, jackbooted fellow who wears a helmet that obscures his eyes and makes him look like a rebel pilot in a Star Wars flick. Like Lucas, he can use PK [Your Favorite Thing] and pull the Seven Needles. He is so similar in appearance to Lucas that his Pigmask subordinates are occasionally prone to mistaking Lucas for him. When he and Lucas meet face to face, Lucas gets a seriously weird feeling.

Rule #23 ("The Melfice Rule") of the Grand List of Console Role-Playing Game Cliches holds that if the male hero has an older sibling, the sibling will also be male and will turn out to be one of the major villains. So I don't think we're supposed to be that shocked when Flint tells us near the climax of Chapter 8 that the Masked Man is actually Claus. Maybe we're supposed to keep on waiting and waiting for the truth to come out, hoping that we're wrong, that there's some other explanation.

We'll talk more about the Masked Man a bit later.

TANETANE ISLAND

Some recreational users of psychoactive drugs are very quick and very eager to claim artists and designers as kindred spirits. More times than I'd like to admit, as a twentysomething student I'd spend whole afternoons sitting around with friends, all of us baked as yammonsters, affirming and agreeing that every single musician who came on the playlist was, like, definitely totally high. It's not that different where video games are concerned. Mario becomes super by eating shrooms, yo. And the game is a bunch of crazy stuff happening in this freaky place called the mushroom kingdom. Miyomoto be trippin'. He knows what up. Shrooms were legal in Japan in the 1980s, yanno? Etc., etc.

Some recreational users of psychoactive drugs are very quick and very eager to claim artists and designers as kindred spirits. More times than I'd like to admit, as a twentysomething student I'd spend whole afternoons sitting around with friends, all of us baked as yammonsters, affirming and agreeing that every single musician who came on the playlist was, like, definitely totally high. It's not that different where video games are concerned. Mario becomes super by eating shrooms, yo. And the game is a bunch of crazy stuff happening in this freaky place called the mushroom kingdom. Miyomoto be trippin'. He knows what up. Shrooms were legal in Japan in the 1980s, yanno? Etc., etc.